People looking for love think they’re looking for someone who is going to make them happy. In reality, we look for what is familiar, even if what is familiar is abuse.

By the time Juan Roman’s girlfriend attacked him with a knife and hammer, it was clear he had found the same unpredictable violence he had endured growing up with an abusive mother. For Juan, these women were bookends to 17 years of homelessness and countless violent aggressions he was victim to on the streets.

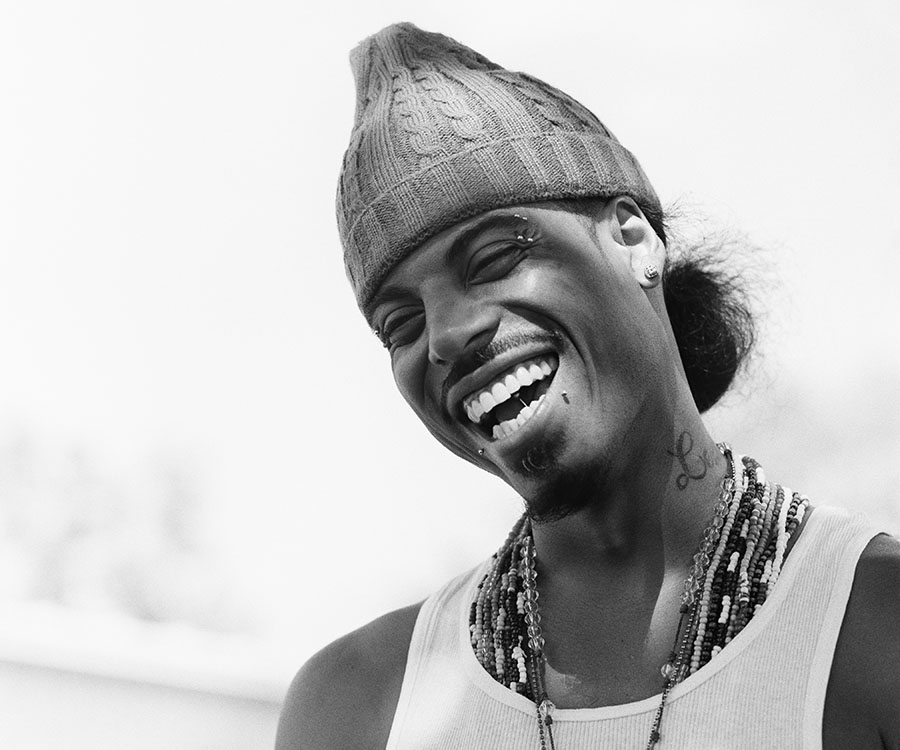

“I looked for the love growing up. I expected it from the people I was with, but the love I was looking for wasn’t there,” Juan says. “That wasn’t fair to me growing up. I raised myself over all those years.”

He slept in cardboard boxes, in subways, in parks, on mattresses pulled from dumpsters. After a childhood of verbal, physical and emotional abuse, Juan’s mom kicked him out when he was 15; he spent the next 10 years living on the streets in New York City.

He came to Rochester in his mid-twenties and found House of Mercy a few years later directly following a suicide attempt.

Juan says, “I was like, ‘OK, I suffer with PTSD; I have anxiety problems; I shake a lot; I have anger problems.’ With all those emotions taking me back to my past, I was asking, ‘What does God want me here for? What’s the purpose?’”

He remembers standing on Lake Ave. “I was looking at the traffic going back and forth. My instinct told me to call 911. But I didn’t call 911; I called 211, the hotline for emergency housing.” A few days later, Juan found himself at House of Mercy.

He was reluctant to go. He had bad experiences with homeless shelters in New York City. But he was thankful to have a place to stay where he could heal from his injuries, years of being jumped by gangs, car accidents, beatings from people looking to steal what few belongings he carried with him.

Juan never panhandled, he says. He never begged for food. It was his pride that maintained this distinction between Juan and other homeless people. It also was his pride that kept him from asking for the help he so sorely needed. By the time he got to House of Mercy though, he was ready.

“Nobody abused me here,” Juan says. “I had the support from House of Mercy. That was the love and compassion they give out.” House of Mercy also helped Juan get an original copy of his birth certificate; they helped him get his social security number, his state ID, insurance and most recently a driver’s license.

“That took a minute. I never knew I would have my permit because of me having a reading problem. The highest grade I completed was 8th grade, so I have trouble comprehending some words,” Juan says. Two and a half years after finding House of Mercy, Juan has turned his life around and looks to help others do the same.

He remembers a family of four from Puerto Rico, displaced after Hurricane Maria. Juan was their translator. He went with them to the Department of Social Services; he helped enroll their children in school. He helped them find housing and moved them into their first apartment in Rochester.

Growing up, anything can happen, Juan says. He tells that to the groups of high schoolers and even legislators he speaks to through House of Mercy. At first, he would cry when he shared with them what it was like growing up on the streets with no one to rely on. Now, he’s pushed past some of that pain to do the good he realizes he’s here to accomplish.

“When I was homeless for 17 years, I (couldn’t imagine) that today I would be helping and doing the services I do now. My mentality was, ‘How can I get out of the (situation) I was in?’” Juan says. “I came to realize over the last two and half years it was here: I had it all the time. I just couldn’t see it because of my rage, of me being homeless, and me being me trying to survive for all of those years.”

Today, Juan has his own apartment, his own car—the independence he dreamed of since his mother threw him out nearly two decades ago. He owes it to the love he finally found at House of Mercy.

Juan’s story is part of a rippling effect of radical compassion—a term at the heart of a new project at House of Mercy, where local storytellers document how people like Juan make use of their suffering to help people in need.