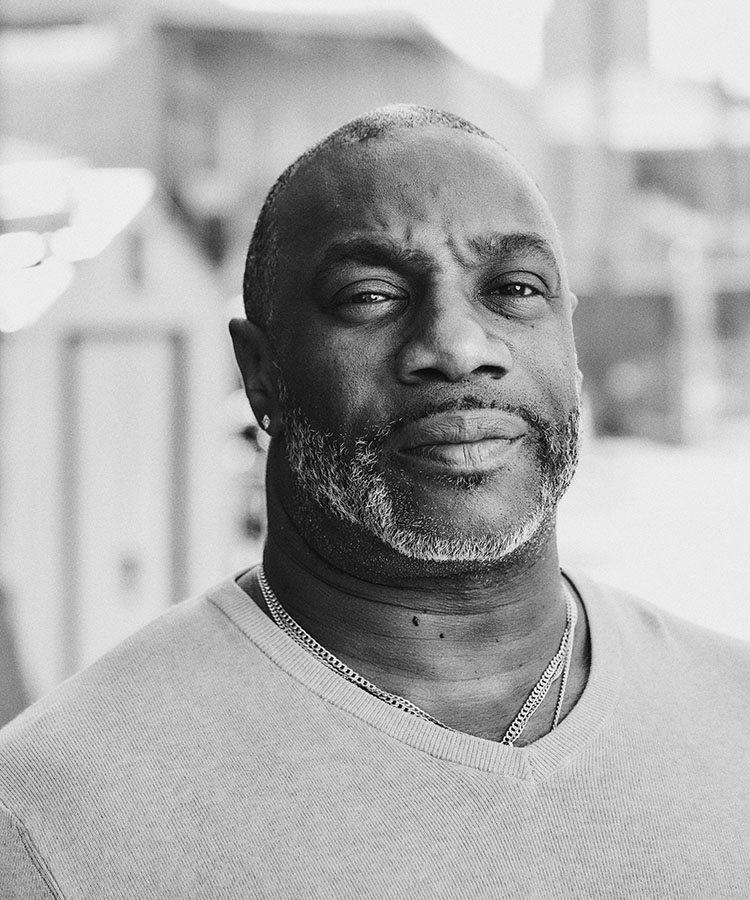

By the time he spent his first night at the House of Mercy six years ago, Earl Thomas’s heart was bone dry.

He had spent nearly 30 years addicted to drugs and alcohol. Earl always found a place to land—with a friend or family member. By this time though, he had burned all those bridges.

Going to House of Mercy, Earl says, helped him see himself and finally find the focus to change.

“God put House of Mercy in my life to walk through a door with people just like me, men and women,” he says. Seeing them, he says, helped him break up with his addiction, which was his longest-standing relationship in a life overshadowed by loss.

Earl’s father died when he was three months old; his mother was murdered in their kitchen when he was nine. No one ever spoke about her death or the man who broke in during a card game to steal their money. As a boy, he had to come to his own conclusions. His sister took him in to raise with her children.

“Her boyfriend was a pimp and a drug dealer. That was my lifestyle,” Earl says. “So, as far as having someone to believe in me… I never did.

“I hung out with the kids on the street, and they became my family. I wanted to fit in and feel part of the crowd. So, that’s how I started selling drugs and using drugs. That’s when the merry go round started,” Earl says. “I was 16 when I first started smoking reefer and selling drugs. When I stopped, I was 45.”

Before finding himself homeless, Earl had worked doing laundry at the House of Mercy; the night he found himself homeless, he wondered if Sister Rita or Sister Grace might remember him and let him stay. Here, Earl remembers that time in his life:

“I think some things happen for a reason. I think my blessing was, not the addiction, but by losing my (home), I was able to come to the House of Mercy. I was able to actually focus,” he says. “I had people here to help me. I couldn’t believe that Sister Rita and Sister Grace would let me stay even with my addiction.”

When asked what he means by focus, Earl says: “I had to come up with a plan for my life. ‘Do I want to keep using drugs?’ Part of me wanted to. Part of me wanted to see if there was a better way of living. So, I actually stayed. I continued to do the laundry. Sister Rita and Sister Grace actually called me into their office and told me there was a facility.

Here, Earl’s voice breaks.

It was two weeks before they found a place, and Earl didn’t quite believe it would happen. In addiction, he says, you don’t believe in anything else.

“You don’t trust anyone,” Earl says. “You are only out for yourself. You’re doing things that aren’t right. When they told me (they had a place for me), part of me believed them, and part of me didn’t.

“When Sister Rita came and actually took me to a local facility, she told me, ‘Good luck.’” Here, Earl pauses. “I think that gave me the hope that, ‘Earl, you can do it.’ Because I never had people believe in me.”

Since that moment six years ago, Earl has been sober. He has a newspaper route now, and he volunteers for the House of Mercy, giving back to help the very people who first helped him.

Earl runs a self-improvement group where he counsels residents at the shelter. He also serves as a liaison for residents to connect with doctoral students studying to become psychologists at Rochester Institute of Technology.

He says he is touched when he sees a resident find the hope that springs from someone else’s care and sincerity. He sees that between the residents and counselors and remembers how those precious drops of respect six years ago changed his life so deeply and opened his heart for good. It’s the rippling effect of radical compassion.